Key Findings

The New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis) can benefit from surrogate species management – a conservation approach benefiting a broad suite of species that occupy similar habitat, with the surrogate species referring to the individual plant, animal or insect that is the focus of conservation and represents a broader set of species. This was determined after researchers found that at least 12 shrubland-obligate birds occupy the same shrubland habitat as the at-risk New England cottontail.

About the Co-Author

Adrienne Kovach, Associate Professor of Natural Resources and the Environment

Contact information: Adrienne.Kovach@unh.edu, 603-862-1603, Kovach Lab website

This research first published in Ecosphere.

Researchers: A. Kovach, M. Bauer, and K. O'Brien

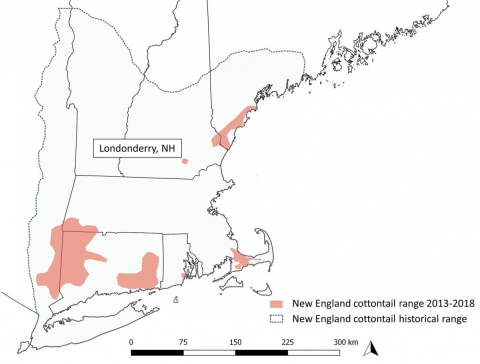

In New England, land use has changed dramatically over the past century, due largely to residential development and the breaking up and abandonment of farmlands. An unintended impact has been a more than 86 percent decrease in the range of the New England cottontail. The New England cottontail requires habitats of shrublands and young forests with dense understories and thick brush, where it can easily escape from predators, build nests and find its preferred diet of grasses and flowering plants and shrubs. Ongoing habitat restoration efforts will help the survival of the New England cottontail, and new research by COLSA researchers published in Ecosphere finds that these efforts will have far-reaching benefits to 12 shrubland-obligate bird species with which the cottontail shares its habitat.

The bird species include the Yellow Warbler, Prairie Warbler, Eastern Towhee, Black-and-White Warbler, Brown Thrasher, Field Sparrow, Blue-winged Warbler, Alder Flycatcher, Gray Catbird, Song Sparrow, Indigo Bunting and American Goldfinch. From 2015 to 2016, UNH researchers Adrienne Kovach and Melissa Bauer '18G, and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service biologist Kathleen O’Brien, surveyed 28 patches (in Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts) that were occupied by or managed for the New England cottontail and inventoried the number and species of birds present and the specific microhabitat characteristics of each site. In their research, they found that diverse modes of habitat management for New England cottontails takes place on a variety of site types and successional stages, thereby benefiting specialist birds with a range of habitat affinities across multiple stages of shrubland growth.

The New England cottontail’s range extends from Southern Maine to Southeastern New York, with remnant occupied habitat patches in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. Its historical range also included southern Vermont. Since the 1960s, the population of the New England cottontail has declined due largely to habitat loss and fragmentation, as well as competition with the introduced Eastern cottontail. Today, it’s believed there are less than 100 New England cottontail living in New Hampshire and less than 10,000 alive in the wild altogether. Since 2011, over 13,000 acres of shrubland habitat have been restored or maintained for the New England cottontails, and biologists from the New England Cottontail Technical Committee, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Hampshire Fish and Game aim to restore another 30,000 acres of New England cottontail habitat by 2030.

Shrubland-obligate birds that share habitat with the New England cottontail. Top row ltr: Yellow Warbler, Prairie Warbler, Eastern Towhee and Black-and-White Warbler. Middle row ltr: Brown Thrasher, Field Sparrow, Blue-winged Warbler and Alder Flycatcher. Bottom row ltr: Gray Catbird, Song Sparrow, Indigo Bunting and American Goldfinch.

“We’re putting all this effort into creating habitat, so it’s nice to know that even if we create these habitats and the New England cottontail doesn’t end up occupying some of it, that a suite of other animals will use it,” says Kovach, who’s been studying New England cottontails since 2001. “And although we only surveyed birds, there are other shrubland-obligate species, like pollinators and reptiles, that could occupy these spaces.”

This material is based on work supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (under Hatch award number 1023445) and the state of New Hampshire. Co-authors include A. Kovach, M. Bauer and K. O'Brien.