This research was published in the INSPIRED: A Publication of the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station (Spring 2024)

Researchers: A. S. Wymore, M. D. Shattuck, J. D. Potter, L. Snyder & W. H. McDowell

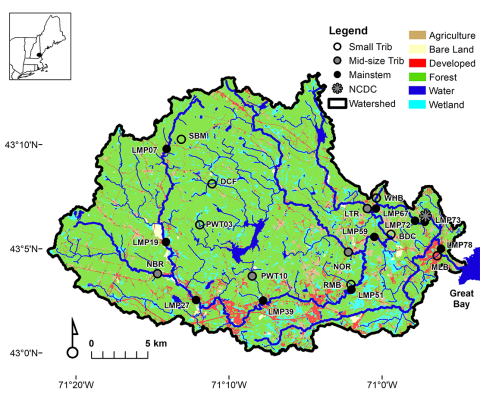

From its headwaters near Northwood Meadows State Park in Northwood, NH, the Lamprey River meanders for more than 50 miles until it empties out into New Hampshire’s Great Bay estuary. Like many rivers in the state, the Lamprey River—and nearly a dozen tributaries that empty into the Lamprey River—moves through forested regions and agricultural lands as well as through municipal downtowns and a variety of mixed-use and suburban landscapes. This diversity of landscapes enables the opportunity to assess how changes in land use and land cover impact water quality over time.

Background and Key Concepts

The Lamprey River Hydrological Observatory (LRHO) has collected more than 20 years of data describing the chemistry and hydrology of the 212-square-mile Lamprey River watershed, providing a baseline of data on river and stream discharge, levels of nitrogen and greenhouse gases (including methane and nitrous oxide), and dissolved organic matter. These data offer a historic look at how a developing landscape and warming climate have affected the watershed as well as a comparison of future climate change-based measurements.

As a result, the data set can be used to identify different trends, such as quantifying how a loss of forest cover—due largely to suburban development—has resulted in increased levels of nitrate found in the Lamprey River’s tributaries, which span a range of forest cover levels (Fig.1).

Long-term research of the Lamprey River can provide particularly impactful insights. Its partial protection under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and passage through areas growing in population density—where most households use on-site waste disposal, such as septic systems, that can pass nitrogen into water runoff—offer conditions for studying the impact of suburbanization on a major water body. The river’s location in a temperate region, where winters are experiencing less snow and more rain than they did two decades ago and the transitional seasons between winter (spring and fall) are lengthening, make it an ideal watershed for studying climate change impacts.

The study’s length also allows sufficient data to characterize river dynamics following extreme weather events, including multiple record-breaking winter and summer droughts; consecutive 100-year-scale floods (in 2006 and 2007); and shifting seasonal changes such as shorter winters and longer springs.

Additionally, the analyses can identify changes in the chemistry of surface water within the watershed over time, such as determining the extent to which nitrate levels within the river and tributaries are slowly rising while dissolved organic nitrogen is steadily decreasing. However, how this will impact downstream waterbodies, like the Great Bay estuary, remains largely unknown.

Key Findings

- Monitoring data from more than 20 years indicate rising nitrate levels and changing water chemistry in the Lamprey River watershed in New Hampshire, likely linked to increased suburbanization.

- River dynamics reflected climate shifts, with more rain, less snow, and altered seasonality occurring over the last two decades.

- Cleaner precipitation but increased nitrogen pollution is impacting downstream estuarine health of New Hampshire’s Great Bay.

About the Co-author

Adam Wymore, Associate Professor of Natural Resources and the Environment

Contact information: Adam.Wymore@unh.edu, FindScholars profile

Fig. 1. Land use map of the Lamprey River watershed, depicting forest, agriculture, wetland, water, and developed areas. The map supports research on how suburban expansion and land use changes influence water quality and ecosystem health.

Methodology

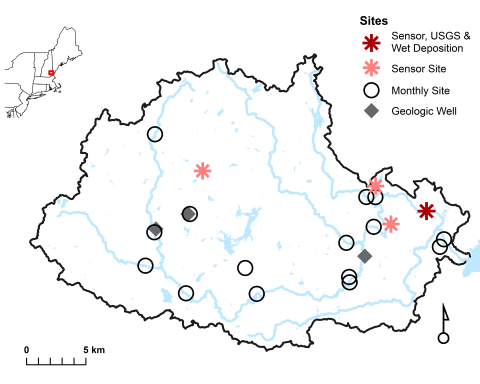

Traditional water sampling has occurred since 1999, with samples being collected from over 20 sites weekly or monthly (Fig. 2). In 2013, a series of high-frequency remote sensors were installed throughout the watershed to provide continuous data on water nutrient levels. Sending data transmissions every 15 minutes, these sensors collected data throughout New Hampshire winters, whereas similar water quality studies in similar climates often remove their sensors during the winter months.

Additionally, because of their multi-probe design, these sensors can collect an array of statistics, including nitrate and dissolved organic matter concentration, pH levels and temperature, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and more. This offers a more complete, real-time characterization of conditions in the rivers and streams.

The dual monitoring approach enabled creating a detailed and dynamic picture of the Lamprey River over an extensive period. The weekly samples offered a longitudinal dataset, allowing for the tracking of changes and trends that might otherwise be lost in less frequent sampling. The high-frequency sensor data provided the granularity necessary to understand the river’s responses to short-term events and seasonal variations.

Figure 2. Map of the Lamprey River watershed showing sensor sites, monthly grab sample locations, and geologic wells. These sites provide high-frequency data on water quality and hydrology, aiding research on suburbanization and climate impacts.

These data were also used to examine fluxes of greenhouse gases—including methane and nitrous oxide—thereby contributing to an understanding of the watershed’s role in broader climate patterns. Additionally, the nested-watershed design facilitated an analysis of the spatial variability across the watershed, ensuring a thorough understanding of the different forces at play in the various sub-environments within the river system.

Results and Impacts

The data from the Lamprey River show clear signs of the surrounding area’s suburban growth affecting water quality. Higher levels of nitrate have been consistently recorded, suggesting that as the region develops, the water quality is changing. This trend is concerning because nitrate can be harmful to aquatic ecosystems and human health.

At the same time, there’s been a notable decrease in dissolved organic nitrogen, which could affect the river’s natural processes. Furthermore, the climate patterns around the Lamprey River are shifting. Winters have become shorter and springs longer, and the region is experiencing more extreme weather, including severe droughts and floods. These conditions stress the river system and can lead to longer-term impacts on water quality.

Implications for the Future

This study points to a need for strategies that can handle the likely effects of higher residential density and changing weather and climate patterns. Furthermore, the health of the Great Bay estuary, which the Lamprey River is the largest river contributor to by water volume, depends on understanding and managing these changes effectively. This ongoing research provides important checkpoints that can help us see how human activities and climate patterns affect the Lamprey River, and this understanding is crucial for making informed decisions about managing watersheds, freshwater resources and the environment more broadly.

This material is based on work supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (under Hatch award number 1022291 and 1019522) and the state of New Hampshire.