Key Findings

The decision to not list the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis) under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 2015 was attributed to the perceived success of ongoing conservation efforts, as evaluated by the Policy for Evaluation of Conservation Efforts (PECE) analysis. In the seven years since, despite substantial collaborative efforts by the members of the New England Cottontail Conservation Initiative and other stakeholders, the remaining population of New England cottontail in the Northeast has only declined further, nearing closer to total extinction. This situation demonstrates the pitfalls of using the existence of cooperative conservation efforts rather than the outcomes of species status assessments as the basis for ESA listing decisions.

The three-step Species Status Assessment (SSA) was developed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service for providing foundational science that informs ESA decisions. For a species with a severely declining trajectory, when the outcome of this quantitative assessment is over-ridden by the outcome of a PECE analysis, there may be negative impacts on the species recovery. To avoid such a scenario, if the SSA finds that a species warrants protection because it’s at risk of extinction, this information should be presented clearly and transparently to all stakeholders and considered independently of a PECE analysis.

Two resolutions could help facilitate the listing of “at-risk” species, like the New England cottontail, in the face of concerns about the regulatory burdens of the ESA:

- Remove the stigma of failure from listing by redefining “recovery” to not depend on delisting, and rather to be based on security from extinction. Relax regulations once this security threshold is reached.

- Make use of an existing, but not often used, provision to tailor specific conservation measures for species designated as “threatened”, with less punitive consequences for their conservation. In this way, many at-risk species might qualify for threatened status rather than endangered, thereby enabling cooperative conservation simultaneously with listing under the ESA.

About the Co-Author

Adrienne Kovach, Associate Professor of Natural Resources and the Environment

Contact information: Adrienne.Kovach@unh.edu, 603-862-1603, Kovach Lab website

This research first published in Environmental Management.

Researchers: A. Kovach, A. Cheeseman, J. Cohen, C. Rittenhouse and C. Whipps

Proactive Conservation describes collaborative, voluntary efforts to conserve and restore species before they require government-regulated conservation efforts, such as through the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA). Considered a bottom-up approach to natural resource management, Proactive Conservation emphasizes collaborative decision-making and shared participation. It’s widely used, especially by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service, as a means to motivate communities to enact voluntary actions to conserve at-risk species and thereby avoid the regulatory burdens of the ESA.

While Proactive Conservation is promoted as the current model of conservation and has been applied to the conservation of many at-risk species, it has not yet been evaluated with respect to its outcomes for species status and recovery. The first such evaluation was recently provided by Adrienne Kovach, a scientist with the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station and a faculty member with UNH’s natural resources and the environment department, and her colleagues from South Dakota State University, State University of New York, and the University of Connecticut in an article published in the journal Environmental Management. In the article, Kovach and her colleagues focus their assessment using the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), an at-risk species that has been a priority conservation target in the Northeast for the last decade, as a case study.

Kovach and co-authors examine the history, present status and recovery outcomes for the New England cottontail from a scientific lens, since the 2015 Policy for Evaluation of Conservation Efforts (PECE) decision to preclude the cottontail from ESA listing. They then evaluate the impacts of the PECE decision on the recovery efforts for the New England cottontail and consider how the outcomes may have been different had the species been granted ESA protection. They also consider the benefits and limitations of Proactive Conservation in general, examine the stigmatization around listing species with the ESA, and present a new potential definition of species in “recovery” that doesn’t require removing them from ESA listing.

"The collaborative efforts under the Proactive Conservation paradigm have numerous benefits for communities and the species they seek to recover; however, the efforts and activities themselves must not be conflated with species recovery outcomes," said Kovach. "While voluntary conservation efforts are valuable and should be rewarded, they should not be used to avoid the law of the ESA, which requires listing a species with a severely declining trajectory."

Ultimately, we must use science and quantitative metrics related to species viability to make realistic determinations about species status, and provide those species determined to be endangered with the protection they are guaranteed under the ESA.

"Ultimately, we must use science and quantitative metrics related to species viability to make realistic determinations about species status, and provide those species determined to be endangered with the protection they are guaranteed under the ESA. Our assessment calls into question the decision not to provide ESA support to the New England cottontail."

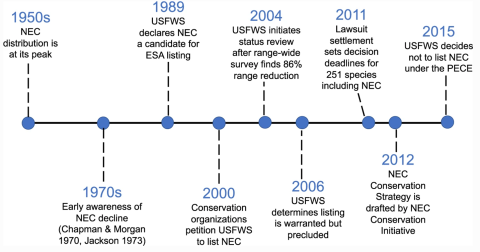

A timeline of events leading to the 2015 USFWS decision not to list the New England cottontail (NEC) under the Endangered Species Act.

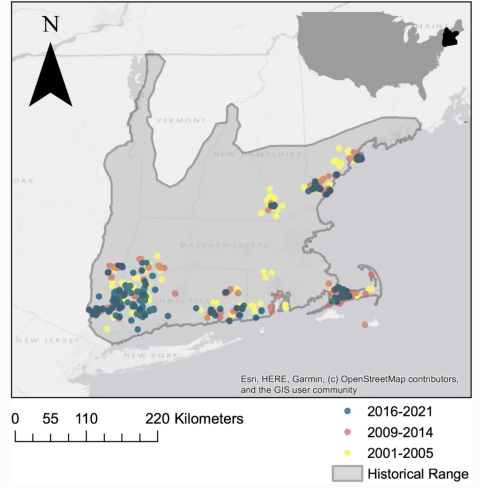

A map showing decline of New England cottontail distribution in the northeastern United States.

Funding was provided by the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station, through a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture McIntire-Stennis Project #1006964 and 1023445. This is manuscript #2950. Additional funding was provided by grants from the Center of Biological Risk, University of Connecticut, and the Regional Pittman-Robertson-funded New England Cottontail Initiative. Co-authors include A. Kovach, A. Cheeseman, J. Cohen, C. Rittenhouse and C. Whipps