This research was published in the INSPIRED: A Publication of the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station (Fall 2024)

Researchers: M. Edwards, A. Villeneuve, B. Jellison and E. R. White

Shellfish, both farmed and wild, are increasingly experiencing physiological stress due to the impacts of climate change, nutrient pollution, and invasive species on coastal marine systems. Traditional assays of stressor impacts using physiological experiments can identify the consequences of simple interactions on shellfish and expected trends from increasing environmental disturbance. However, the results from these approaches fail to accurately identify stressful conditions in coastal environments. Coastal managers and shellfish farmers require real-time information about how shellfish are responding to current conditions to make decisions that protect human, environmental, and economic health.

Fig. 1. Oyster biosensor prototypes being tested.

Background and Key Concepts

The Gulf of Maine is changing rapidly, marked by rising surface temperatures and heightened occurrences of coastal acidification events driven by freshwater inflow. Within the Gulf of Maine, Great Bay is a semi-enclosed and tidally influenced estuary in New Hampshire that is the epicenter of oyster aquaculture efforts in the state. Overall, oyster aquaculture contributed $4.6 million in economic benefits to the State of New Hampshire in 2020 and has expanded 774% since 2013.

However, wild oyster populations have continued to decline despite restoration efforts. Invasive species like European green crabs have also become more prevalent in the region, adding new stressors to already vulnerable oyster populations by affecting their behavior and survival. These changes pose challenges for both wild and farmed oyster populations, and the long-term sustainability of this aquaculture industry.

Fig. 2. A biosensor-equipped oyster in a controlled tank experiment, with a crab placed nearby to assess oyster responses to predator cues.

Methodology

In 2023 and 2024, researchers developed a series of oyster biosensor prototypes (Fig. 1) to monitor oyster health in both lab and field settings. In the lab, the system was tested by exposing oysters to invasive European green crabs (Fig. 2) to observe gaping behavior—the degree to which oysters open—after a week-long habituation period. The research assessed the impacts of environmental stressors such as high temperatures, low dissolved oxygen, and extreme pH levels on oyster behavior, growth, and survival. This provided an opportunity to understand oysters' complex responsiveness to multiple stressors in real time.

For field deployments, biosensors were placed at oyster farms in Little Bay, New Hampshire. The sensors measured oyster health continuously, linking behavioral responses—like changes in gaping behavior—to environmental variables such as temperature fluctuations and water quality.

Key Findings

- Eastern oysters are affected by multiple stressors, including warmer waters and invasive species like European green crabs.

- Biosensors attached to oysters can measure oysters' gaping behavior in real time, enabling a more accurate understanding of their responses to stressors.

- Oysters have the greatest response to predator cues at nighttime and exhibit higher stress in high temperatures, low dissolved oxygen, and extreme water acidity levels.

About the Co-authors

Easton White, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences

Contact information: Easton.White@unh.edu, FindScholars profile

Brittany Jellison, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences

Contact information: Brittany.Jellison@unh.edu, FindScholars profile

Discussion of Findings

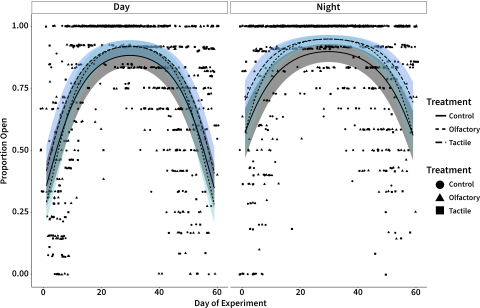

The research findings highlight the complex interactions between oyster behaviors and both environmental stressors and invasive predators. In lab-based research, oysters exposed to predator cues from European green crabs showed increased gaping behavior, particularly during nighttime (Fig. 3). This change in behavior may initially seem beneficial, allowing for more feeding and respiration, but it also leaves oysters vulnerable to poor water quality or additional stressors.

Fig. 3. Percentage of time spent gaping for all three treatments for daytime and nighttime. For treatment types, olfactory refers to a crab and oyster in same container but physically separated, whereas tactile refers to a crab and oyster in the same container with crab being able to physically interact with an oyster but not consume it.

For field deployments, biosensors were placed at oyster farms in Little Bay, New Hampshire. The sensors measured oyster health continuously, linking behavioral responses—like changes in gaping behavior—to environmental variables such as temperature fluctuations and water quality.

Discussion of Findings

The research findings highlight the complex interactions between oyster behaviors and both environmental stressors and invasive predators. In lab-based research, oysters exposed to predator cues from European green crabs showed increased gaping behavior, particularly during nighttime. This change in behavior may initially seem beneficial, allowing for more feeding and respiration, but it also leaves oysters vulnerable to poor water quality or additional stressors.

Additionally, oysters subjected to high temperatures, low dissolved oxygen, and extreme pH levels in the lab demonstrated changes in gaping behavior linked to their overall health. In field deployments, oysters stopped filtering and feeding after stressful events, such as heavy rain, suggesting that both predator presence and environmental conditions play a role in oyster behavior and, ultimately, their health.

Strategic Recommendations and Conclusion

The findings indicate that the combined impact of environmental stressors and predatory cues poses significant challenges to oyster survival, particularly in the Gulf of Maine, where green crab populations are increasing. The research shows that oyster responses are dynamic and influenced by a combination of real-time environmental variables, highlighting the need for continuous monitoring to understand the long-term impacts on both wild and farmed oysters.

Oyster farmers and coastal managers should consider the additive effects of predator cues and environmental stressors when developing strategies to protect oyster populations, both wild and farmed, in New Hampshire and beyond. The deployment of biosensors in Little Bay is a crucial step toward achieving real-time insights into oyster behavior and environmental conditions.

Over the next two years, more biosensors will be deployed to further study these dynamics and their implications for both oyster health and water quality management. Additional data will enable researchers and producers to better predict oyster responses to extreme events, such as heatwaves or predator influxes, and implement proactive measures to safeguard the ecological and economic value of oysters. Expanding monitoring systems across more oyster farms could help better prepare and mitigate the risks posed by environmental and predatory stressors, ensuring the resilience of oyster populations in the face of ongoing environmental change.

This material is based on work supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (under Hatch award number 7004018) and the state of New Hampshire.