This research was published in the INSPIRED: A Publication of the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station (Spring 2024)

Researchers: K. E. Clark, R. F. Stallard, S. F. Murphy, M. A. Scholl, G. Gonzalez, A. F. Plante & W. H. McDowell

Rivers in tropical and temperate climates like New Hampshire are often celebrated for their biodiversity and value as ecotourism destinations. But they may also play a more critical function in the Earth’s ecological balance than previously recognized by acting as natural carbon sinks—capturing and preventing organic carbon from converting into carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas. The mechanism by which rivers play this pivotal role is still, however, not fully identified. One factor may be the manner in which rivers carry sediment from inland to the ocean.

Measuring Particulate Runoff

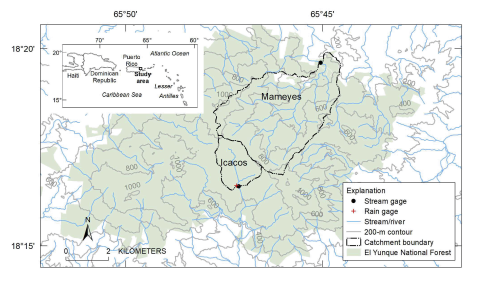

The research team analyzed water samples collected between 1991 and 2015 from the Luquillo Experimental Forest in Puerto Rico’s El Yunque National Forest (Fig. 1), focusing on particulate organic carbon (POC) and sediment concentrations in the river water samples captured following major rainfall events. The researchers quantified the amounts of sediment and POC runoff, which they paired with river discharge data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Using this dataset, they were able to estimate particulate organic carbon yields, shedding light on the rivers’ efficiency in carbon sequestration and the impact of extreme rainfall events on these processes.

Results and Impacts

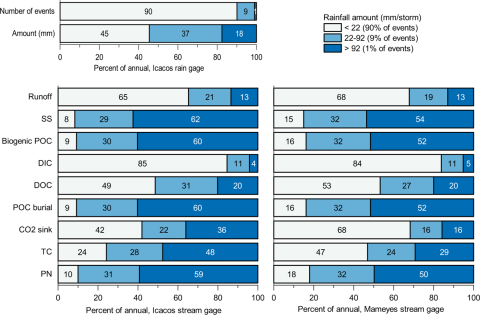

The findings highlight rivers’ remarkable capacity for carbon storage. For rivers emptying directly into the ocean, more than 65% of POC is buried in offshore sedimentary deposits (Fig. 2). This process not only removes carbon from the atmospheric cycle but also highlights the critical role of these waterways in long-term carbon sequestration.

Impact of Extreme Rainfall

Research findings indicate that extreme rainfall events, which are growing more frequent and intense with global warming, are responsible for a significant share (52-60%) of the annual POC export by rivers. This underscores the vulnerability of these ecosystems to climate variability and the crucial role they play in buffering climate impacts.

Reevaluating River Contributions

Findings from this study are helping update the underlying assumptions of prior models, which likely underestimated the contribution of rivers with less erodible, igneous, and volcaniclastic bedrock. These rivers are now recognized as even more integral to the global carbon cycle than previously thought, necessitating a reevaluation of their role in ecological models and conservation strategies.

Implications for the Future

Key Findings

- Tropical rivers act as significant carbon sinks, with over 65% of particulate organic carbon (POC) buried in ocean sediments.

- Extreme rainfall events, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change, contribute to over half of the annual POC transfer from rivers to oceans.

- The research helps place a greater emphasis on the role of rivers in the global carbon cycle and, ultimately, on their climate impacts.

About the Co-author

William McDowell, Professor Emeritus, UNH College of Life Sciences and Agriculture

Contact information: Bill.McDowell@unh.edu

Fig. 2. Percent contribution of annual runoff and river exports by rainfall event size for the Icacos and Mameyes Rivers. Note: These exports are separated by rainfall amount as a percentage of annual total (SS suspended sediment, POC biogenic particulate organic carbon, DIC dissolved inorganic carbon, DOC dissolved organic carbon, POC burial estimated POC burial in ocean if biogenic POCburial efficiency is estimated at 22%, CO2 sink estimated atmospheric carbon sink (POCburial + DIC), TC total carbon (POC + DIC + DOC), PN particulate nitrogen).

To address the broader implications of these findings, it is important to consider the role of temperate aquatic ecosystems, such as those in New Hampshire, in global carbon cycling. The substantial carbon sequestration capabilities identified in tropical rivers suggest similar mechanisms may be at work in temperate zones too, albeit with different dynamics due to the variation in climate and vegetation. These temperate ecosystems, often rich in biodiversity and integral to local hydrological cycles, could also be pivotal in mitigating climate change through natural processes such as carbon capture.

Further research should focus on quantifying the carbon sequestration capacities of New England’s rivers, with particular attention to how seasonal changes and extreme weather events impact organic carbon transport and deposition. Understanding these local dynamics will be essential for developing targeted management practices that safeguard these environments and contribute to broader efforts to mitigate climate change effects.

Fig. 1. Map of the Icacos and Mameyes River catchments in Puerto Rico's El Yunque National Forest, highlighting stream gages, rain gages, and watershed boundaries used in carbon sequestration studies.

This material is based upon work supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station, through joint funding of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 1019522, and the state of New Hampshire.