Documenting the Flora of New Hampshire and Beyond

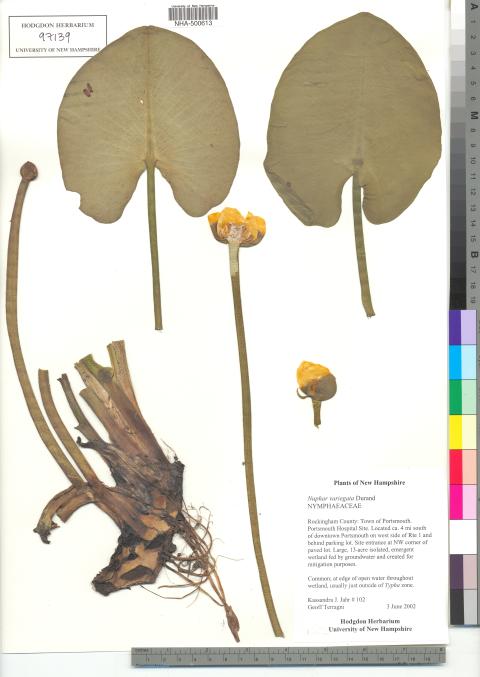

Founded in 1892, the Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium (NHA) at the University of New Hampshire is the largest herbarium in New Hampshire. Its museum-quality collection holds over 206,000 preserved specimens of vascular plants, macroalgae, bryophytes, and lichens, including 98 nomenclatural type specimens. While the specimens serve as physical records of botanical diversity and distribution worldwide, the collections have a strong emphasis on the flora of northeastern North America, Neotropical aquatic species, and marine algae. The Hodgdon Herbarium contains the most complete record of the flora of New Hampshire, supporting taxonomic, ecological, and biogeographic research, as well as education and outreach activities.

Mission Statement

The Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium (NHA) preserves and protects the floristic biodiversity of New England and adjacent Canada, conducts interdisciplinary research that addresses significant regional and national issues, facilitates innovative uses of natural history collections for courses at UNH, and provides engaging outreach to the broader UNH community and public.

More Information

A herbarium is a collection of preserved plant and algal material that is stored, catalogued, and systematically arranged. Each specimen has associated metadata, such as the date of collection, locality, and associated species. The collections serve as a point of reference for plant identification and research and are used by diverse stakeholders such as scientists, biology students, natural resource professionals, landowners, and the general public. Herbaria exchange and loan specimens to other academic and scientific institutions around the world.

The Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium, like all herbaria, is a critical component of scientific infrastructure at UNH, in New Hampshire, and around the world. Herbaria advance scientific discovery and innovation, enrich education, connect communities to nature and science, and preserve Earth’s biological heritage. Herbaria stand alone in providing the temporal, spatial, and taxonomic sampling of plant diversity, preventing loss of knowledge about plant life on Earth.

Herbarium specimens are used to study plant evolution, biology, and ecology, the impacts of climate change and human activity on biodiversity, advance biomedical research, and develop improved crops, biocontrol agents, and pharmaceuticals. An estimated 350 million specimens are housed in a network of over 3000 herbaria across the world in order to facilitate this research.

The immense value of herbaria comes from the specimens themselves, their digitized derivatives, and the collective attributes of each unique herbarium. The physical specimens provide information on macroscopic and microscopic morphology, chemical composition, phenetics, development, and genetics, with most specimens capable of yielding DNA for genome sequencing. The metadata obtained from specimen labels offers documentation of species locality, habitat, abundance, and ecology. High-quality specimen images and digitized label metadata allow researchers to survey specimens en masse, informing morphological variation within a species and changes in distribution and phenology of species across space and time. Each herbarium is a unique, irreplaceable set of specimens that collectively represents a particular geographic region, as well as the research interests of the researchers of an institution. The Hodgdon Herbarium contains the most complete record of the flora of New Hampshire, reflects the legacy of scientific research at UNH, and is an irreplaceable component of the scientific infrastructure of UNH and New Hampshire.

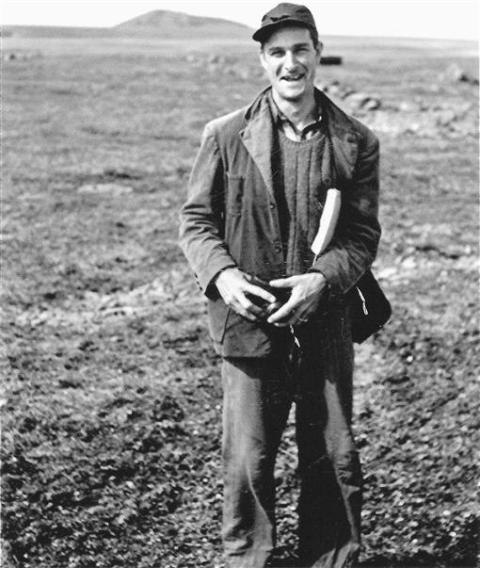

Albion Hodgdon in Alaska, 1952

Image from McGrath, W. E. (2012). Albion Reed Hodgdon: A Life In Botany. Rhodora, 114(958), 163-201.

The Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium (NHA) of was founded in 1892 when the University of New Hampshire, then known as the New Hampshire College of Agricultural and the Mechanic Arts, moved from its Dartmouth College campus in Hanover to its present location in Durham with 1500 specimens. The collection expanded slowly until 1936 when Dr. Albion Reed Hodgdon became the director of the herbarium. An alumnus of UNH, Dr. Hodgdon contributed numerous specimens to the herbarium for his master’s thesis on the Flora of Strafford County, NH. He continued to contribute specimens throughout his career from field work in New England, Alaska, Canada, Mexico, Europe, the Caribbean, and the Galapagos Islands. He had a particular interest in the taxonomy of Rubus and the floristics and phytogeography of coastal Maine and eastern Canada. Dr. Hodgdon oversaw the integration of several “orphan” collections from other herbarium including the permanent loans of 9400 specimens of the Parker Cleaveland Herbarium of Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine and 15,447 specimens from the Portland Society of Natural History, Portland, Maine (now dissolved). Through these loans, NHA acquired 97 invaluable type specimens collected in the 1800’s and early 1900’s by Augustus Fendler, Ferdinand Lindheimer, and Merritt L. Fernald. By the time of Dr. Hodgdon’s death in 1976, the herbarium amassed approximately 82,000 vascular plant specimens and 36,000 specimens of marine algae. In 1978, NHA was officially dedicated in his honor, and its accompanying botanical library was dedicated to Sumner T. Pike, a patron and friend of the herbarium.

Between 1975 and 2009 Dr. Garrett E. Crow served as Director of NHA. His multi-faceted research program included systematic, biogeographic, and floristic studies of rare and endangered species in New Hampshire with a specialty in aquatic vascular plants. Among his many publications, Dr. Crow authored or co-authored New England's Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Plants, Aquatic and Wetland Plants of Northeastern North America, and the taxonomic treatments of several genera and families for the Flora of North America North of Mexico and Manual de Plantas de Costa Rica. He and his students are largely responsible for NHA’s extensive collections of vascular aquatic and neotropical specimens. In 1996 Dr. Crow oversaw the move of the collection from Nesmith Hall to the Spaulding Life Sciences Building and the installation of the space-saving compactor system that doubled the collection’s capacity.

From 1965 to 2017 Dr. Arthur Mathieson oversaw the expansion of the macroalgal collection at NHA, with a strong focus on the macroalgal diversity of coastal New Hampshire and Maine. He personally contributed nearly 46,000 specimens, with a substantial number of additional specimens contributed by his students. Dr. Mathieson served as the Director of the UNH Jackson Estuarine Lab from 1972 to 1982, and many of his collections document the macroalgae of the Great Bay. Among his more than 170 publications, Dr. Mathieson coauthored Seaweeds of the Northwest Atlantic and The Seaweeds of Florida. Currently, the NHA macroalgae collection is the 5th largest in the United States and has the best representation of macroalgal diversity from coastal New England.

Since 2009 Dr. Christopher D. Neefus has served as the director of NHA, serving as PI for several large digitization projects that have resulted in the imaging and databasing of nearly the entire collection. Stemming from his research interests in marine algae and computing, Dr. Neefus headed an NSF-funded consortium of 49 herbaria for the digitization of macroalgae collections that are published on the Macroalgal Herbarium Portal (macroalgae.org), allowing free access to images and data worldwide. Since its establishment, the Macroalgal Herbarium Portal has been used by over 64,000 users in 205 countries. Dr. Janet Sullivan, NHA Collections Manager (2005-2019), oversaw the digitization of the macroalgae collection and the vascular plant collection as part of the NSF-funded Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria (neherbaria.org). Dr. Sullivan’s central involvement in several additional NSF projects have led to the publication of NHA specimens on the data portals of the Consortium of North American Bryophyte Herbaria (bryophyteportal.org), the Pteridophyte Collections Consortium (pteridoportal.org), and the Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria (lichenportal.org). During her tenure, Dr. Sullivan incorporated several important, smaller vascular plant collections including the Keene State College Herbarium, New England College Herbarium, and a portion of Bentley College’s historic teaching collection. By integrating collections by UNH researchers and students, as well as specimens from the NH Natural Heritage Bureau and volunteer groups, Dr. Neefus and Dr. Sullivan have grown NHA to its current size of approximately 120,000 vascular plant, 85,000 marine algae, and 1800 bryophytes and lichens specimens.

In 2021, Dr. Erin Sigel became the NHA Collections Manager, and in January 2024 NHA will move to a newly remodeled collection, processing, and outreach facility in the Spaulding Life Sciences Building.

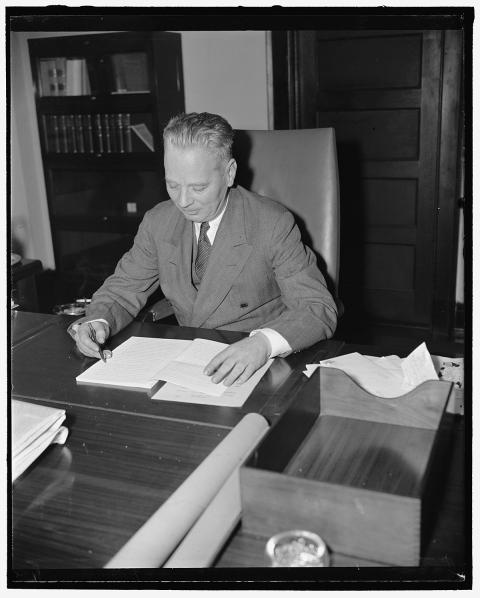

Sumner Pike, 1937

Image: wikipedia

The value and effectiveness of the Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium as a center of botanical activity is greatly enhanced by the supportive arm of its associated library. The strength of the library’s holdings is largely due to the generous financial support of the late Sumner T. Pike. Sumner was very interested in the botanical endeavors of Albion Hodgdon and Radford Pike in the Bay of Fundy, and was especially aware of the value of botanical literature to research efforts. The Sumner Pike Library was dedicated on May 5, 1978. It houses approximately 1500 volumes of botanical references including a worldwide representation of flora and manuals, taxonomic monographs, taxonomic indices, and general references on systematics, phytogeography, ecology, botanical history, horticulture, and wildflowers. Journals and reprints of taxonomic literature are also on file in the library, as are a number of unpublished manuscripts dealing with plants of New Hampshire and Maine.

Researched and written by Kegan Messmer, BIOL 409 Honors Student

Botanical Latin is the internationally recognized standard for naming and describing the world’s thousands of plant species. Botanists worldwide adhere to its specific and complex grammatical standards when contributing to the knowledge of plant diversity. Botanical Latin bridges the language barrier between botanists worldwide, allowing them to collaborate, no matter what their country of origin may be. For aspiring botanists, learning the rules of Botanical Latin can reveal the hidden meaning behind the names of plant species.

Asplenium angustum (Willd.) Presl.

Although Botanical Latin has its origin in the Latin language, it is important to understand that Botanical Latin is not the Latin of antiquity. It has acquired the characteristics of a highly specialized dialect of Latin, or Neo-Latin, the Renaissance-era simplified form of Latin that is primarily used in writing. Since Botanical Latin is not used in everyday contexts, the wide assortment of Latin vocabulary has been repurposed for describing plants exclusively. Thus, Botanical Latin often uses Latin words in a less-literal sense. Botanical Latin essentially inherits the Latin grammar and vocabulary but only uses it for one specific purpose.

The linguistic origins of Botanical Latin date back to ancient Greece. Among others, the Greek author Theophrastus wrote extensive plant descriptions. The names and descriptions of plants created by the Greeks were translated into Latin by the ancient Romans. Pliny the Elder, in particular, translated numerous Greek plant names in his historically valuable work Historia Naturalis. Pliny used a wide range of vocabulary to describe plants, mostly focusing on the parts of plants that had practical uses like stems, shoots and fruits. Ancient Roman descriptions of plants became the foundation for Botanical Latin during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. At this time, using Latin for science was the standard, as there was no other language which was used so ubiquitously in writing that could be understood by scientists across Europe.

Carl Linnaeus, considered the “father of modern taxonomy,” formalized Botanical Latin and distinguished it from other forms of written Latin. Linnaeus was the first to use the binomial naming scheme in taxonomy, which unites terms for genus and species. Linnaeus even created the binomial name for humans, Homo sapiens (‘wise man’). In his work Species Plantarum, Linnaeus provides a binomial for every plant species known to him, organized into genera.

The tradition of Botanical Latin has continued into the present day. Before English became the de facto international language, using Latin when describing new plant species was nothing out of the ordinary. Now, Botanical Latin is largely a formality, cemented as a standard by centuries of precedence. Until 2012, the International Botanical Conference (IBC) required the use of Botanical Latin for names and descriptions of new plant species. Now the IBC permits new species descriptions (but not names) in either Latin or English. This makes it easier for modern botanists to report their findings, as most modern botanists are not proficient in Latin.

The grammar of Botanical Latin does not differ from other forms of Latin. Like other forms of Latin, the vocabulary of Botanical Latin includes nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Since Botanical Latin is not only used to name plant species, but also to write their descriptions, all these parts-of-speech are necessary. Verbs are conjugated with word-endings corresponding to different tenses, person, and number. Unlike English, Latin nouns and adjectives use different word-endings depending on the context in which the word is being used. Nominative case is used when a word is the subject of a sentence. Accusative case is generally used when a word is the direct object in a sentence. Genitive case generally substitutes the word ‘of’ in English. For example, the word flos means ‘flower’; the genitive case of flos would be floris (‘of the flower’). Other cases include the vocative case (used when addressing someone or something, like calling out a name), the dative case (used similarly as the indirect object in English, generally corresponding to the word ‘for’), and the ablative case (used in a variety of contexts, but loosely means ‘with’).

Names of taxonomic groupings follow other patterns which are not solely grammatical. All plant phyla end in the suffix -phyta, which originates from the Greek word phuta (‘plants’). Classes end in -phyceae for algae, from the ancient Greek word phukos (‘seaweed’). Other classes end in -opsida, from the ancient Greek word opsis (‘appearance’). Orders end in -ales, the Latin equivalent of the English suffix ‘-al’. All families end in -aceae, which roughly means ‘resembling’. Genus and species names do not have specific suffixes. Genera are Latin nouns, and species are usually adjectives. Sometimes a species name is a noun fulfilling the role of an adjective. If the species name is an adjective in the grammatical sense, it must agree with the genus name in gender.

Now that the basic rules have been established, we can look at a real-world example of a plant species, present at the Hodgdon herbarium. The northern lady fern, Athyrium angustum, is abundant in the forests of New Hampshire. The genus name Athyrium is derived from the prefix a- (‘without’) and the word thyrium, a latinization of the Greek word thyreos (‘shield’). The namesake of the genus is its seemingly invisible indusia, which cover the spore-producing sori on the undersides of fern leaves. The species name angustum means ‘narrow’ and differentiates the northern lady fern from other lady ferns. The namesake of the species is its narrow fronds, or leaf structures, compared to other lady ferns.

For a more in-depth look at Botanical Latin, its history, and conventions refer to Botanical Latin by William T. Stearn, an essential reference handbook for botanists for decades. Stearn’s Botanical Latin is available online through Archive.org or Amazon.com. A copy also resides at the UNH Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium.

The Hodgdon Herbarium welcomes visiting scientists from other colleges and universities and federal, state, and private agencies. Those wishing to conduct research in the herbarium should contact the Collections Manager, Dr. Erin Sigel (erin.sigel@unh.edu), beforehand to ensure access and availability of the facilities. All incoming specimens will be frozen before being allowed in the main collections room.

Tours and information sessions are offered for UNH classes, local schools, and other educational groups by appointment. Please contact the Collections Manager to make arrangements.

Those interested in volunteer opportunities should contact the Collections Manager. Typical tasks include specimen data entry, mounting and labeling, and scanning specimens for our Virtual Herbarium project. Volunteers with expertise in specimen identification are also welcome.

GIVE TO THE HODGDON HERBARIUM

Your gift to the Albion R. Hodgdon Memorial Fund will support research and education at the Hodgdon Herbarium!

Hours of Operation

Monday - Friday 9 a.m to 5 p.m by appointment.

Contact Dr. Erin Sigel, Collections Manager: erin.sigel@unh.edu Closed for University holidays and during field season.

The herbarium is located in room 133 in Putnam Hall.

No food may be brought into the collections facility.